From MCP-UI to MCP Apps: Evolving Interactive Agent UIs

MCP-UI is fun. It’s scrappy. It’s early. And like I said in my last post, there’s something genuinely addictive about building this close to the edges of an ecosystem while everything is still taking shape.

But MCP Apps feels different.

Not in a “shiny new feature” way. More in a “this is the ecosystem maturing” way.

I recently migrated one of my existing projects, my Cloudinary MCP-UI server, over to an MCP App. And I want to walk through what that process actually looked like in practice, what changed, what surprised me, what broke, and why this change feels meaningful beyond just new syntax.

The starting point: a real MCP-UI server

If you’ve seen my earlier post about turning MCP servers into interactive experiences, you’ve already seen this project.

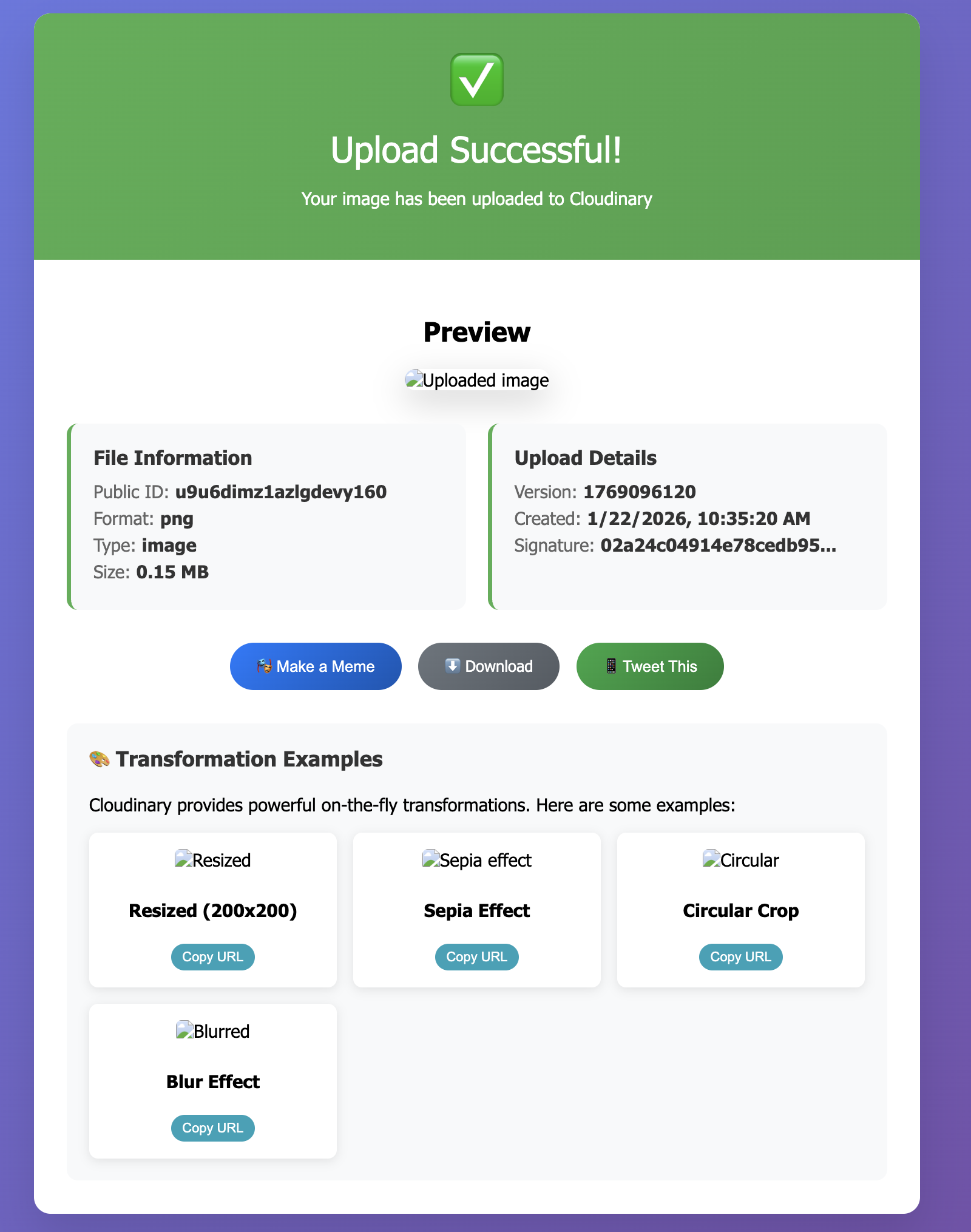

My Cloudinary MCP server returns a rich, interactive UI directly inside my agent’s window after uploads. Instead of a block of JSON, I get something I can actually interact with:

- Image and video previews

- Copyable URLs

- Download buttons

- Transformation examples

- “Make a meme” and “Tweet this” actions

At this point, everything already worked. The experience felt good to use. It looked how I wanted it to look.

So the natural question is:

if I already have the UI experience I want… why change anything?

Why I decided to take this further

The short answer: portability.

As powerful as MCP-UI is, it’s still very much host-specific. It works beautifully inside goose, but the question that kept sitting in the back of everyone's mind was:

What happens when I want this same UI to work somewhere else?

Like inside ChatGPT Apps? Or another agent host entirely?

Right now, MCP-UI is tightly coupled to how a specific client renders UI. That’s fine for experimentation, but it does put a ceiling on how reusable these experiences can be.

That’s the gap MCP Apps is aiming to solve.

What MCP Apps actually changes

Visually, almost nothing changes. The UI looks the same. The interactions feel the same. If you’re just using the tool, you wouldn’t know anything shifted.

The difference is architectural.

With MCP-UI, the mental model is simple: a tool runs, returns UI inline, and the host renders whatever comes back. With MCP Apps, that model changes. Now the tool runs, returns a pointer to the UI, and the host explicitly fetches that UI as a resource and renders it more like a real web application.

Instead of treating UI as just another chunk of output, MCP Apps treats it as its own first-class resource.

That shift sounds subtle, but it changes what’s possible. It means the same UI can travel across different hosts instead of being tightly coupled to one client. It makes the boundaries clearer between what the tool does and how the interface is delivered. It introduces a real security model instead of relying on best-effort conventions. And it pushes the ecosystem toward shared patterns instead of every project inventing its own messaging protocol.

The end result is that MCP Apps feels less like a clever hack that happens to work in one place, and more like infrastructure the ecosystem can actually build on long-term.

How I approached the migration

I didn’t migrate my existing server in place.

Instead, I kept both versions side-by-side:

src/

index.mcp-ui.ts # original working version

index.mcp-app.ts # new MCP Apps version

This wasn’t because git can’t handle reversions — it was purely a workflow choice.

I wanted to be able to:

- Run both implementations back-to-back

- Compare behavior, not just code

- Demo both versions live

- Keep a working reference while I experimented

It made the differences much easier to understand, especially while I was still forming my own mental model of MCP Apps.

The pattern shift: UI stops being inline

This was the moment where everything finally clicked for me.

With MCP Apps, UI stops being something your server returns and starts being something your server serves. That sounds like a small distinction, but architecturally it’s a big shift.

Instead of attaching UI directly to the tool response, your server now takes on a slightly different role:

- It stores the UI under a

ui://URI - It exposes that UI through resource handlers

- And the host fetches it the same way it would fetch a real web app

Once I understood that, everything else started to make more sense.

You’re no longer just “sending UI back with a response.”

You’re building something closer to a tiny UI server that your agent knows how to talk to.

And that shift is exactly what MCP Apps is formalizing.

The 4 key changes when moving from MCP-UI to MCP Apps

This wasn’t a rewrite. It was a structural shift.

Here’s what actually changed, what it meant in practice, and what I had to touch in my own code.

1. UI becomes a resource, not part of the tool response

With MCP-UI, the UI was part of the tool response. I used createUIResource(...) and returned it directly inside content[].

With MCP Apps, that pattern flips.

Instead of returning UI, I now:

- Store the generated HTML under a

ui://URI - Return a pointer to that UI using

_meta.ui.resourceUri - Let the host (like goose) come back and fetch it separately

Here’s what that looks like in my server:

private uiByUri = new Map<string, string>();

const uri = `ui://cloudinary-upload/${result.public_id}`;

this.uiByUri.set(uri, this.createUploadResultUI(result));

return {

content: [

{ type: "text", text: "Upload successful!" }

],

_meta: {

ui: { resourceUri: uri }

}

};

Instead of shipping UI directly inside the response, I’m now effectively saying:

“The UI lives over here. Come fetch it when you’re ready.”

That single shift is the core of MCP Apps.

2. Your server must support resource discovery

Once UI becomes a resource, the host needs a way to actually find it and fetch it.

That means your server has to explicitly opt into supporting resources.

The first change happens right when you create the server:

this.server = new Server(

{ name: "cloudinary-server", version: "1.2.0" },

{

capabilities: {

tools: {},

resources: {}, // 👈 This is required for MCP Apps

},

}

);

If you forget this, your resource handlers won’t even be considered. The host won’t ask for resources because your server never declared that it supports them.

After that, you implement the two required handlers:

ListResourcesRequestSchema→ tells the host what UI resources existReadResourceRequestSchema→ returns the actual HTML when the host asks for it

And your resources must return this MIME type:

text/html;profile=mcp-app

That’s the signal that tells any host:

“This isn’t just text. This is an MCP App.”

Here’s what that looked like in my cloudinary server:

capabilities: { tools: {}, resources: {} }

this.server.setRequestHandler(ListResourcesRequestSchema, async () => ({

resources: Array.from(this.uiByUri.keys()).map((uri) => ({

uri,

name: "Cloudinary UI",

mimeType: "text/html;profile=mcp-app", // This is what makes your UI discoverable across hosts.

})),

}));

this.server.setRequestHandler(ReadResourceRequestSchema, async (req) => ({

contents: [{

uri: req.params.uri,

mimeType: "text/html;profile=mcp-app",

text: this.uiByUri.get(req.params.uri)!,

}],

}));

That combination of declaring resources: {} and implementing these handlers, is what turns your MCP server into something that can actually serve UI as an app instead of just returning blobs of content.

3. CSP becomes your responsibility

This one caught me off guard.

When I first wired my Cloudinary MCP App into goose, everything looked perfect… except the images.

Layout? Fine. Buttons? Working. UI? Beautiful.

But every image was broken.

At first, I assumed something was wrong with Cloudinary. But the URLs worked perfectly when I opened them directly in the browser.

The real issue was CSP (Content Security Policy).

MCP Apps run inside a sandboxed iframe with much stricter security than MCP-UI. By default, external resources are blocked. That means no external images, no external fonts, no external scripts unless you explicitly allow them.

Since my UI loads assets from:

https://res.cloudinary.com

I had to tell the host that this domain was safe.

Here’s what that looked like in my actual server code:

return {

contents: [{

uri,

mimeType: "text/html;profile=mcp-app",

text: html,

_meta: {

ui: {

csp: {

resourceDomains: ["https://res.cloudinary.com"],

connectDomains: ["https://res.cloudinary.com"]

}

}

}

}]

};

As soon as I added that, all my images loaded instantly. MCP Apps isn’t just about shipping prettier UI. It’s introducing real security boundaries around UI execution.

4. UI communication becomes standardized

This change is easy to miss while you’re coding it, but architecturally it’s one of the biggest shifts.

With MCP-UI, my UI talked to the host using custom message types like:

type: "prompt"

type: "ui-size-change"

type: "link"

It worked, but it's not a standard.

MCP Apps replaces that with standardized JSON-RPC methods:

ui/initializeui/messageui/notifications/size-changedui/notifications/host-context-changed

Instead of sending messages and hoping the host understands them, there’s now a shared contract for how UI and host communicate.

Here’s what that actually looked like in my code.

Before (MCP-UI): My “Make a Meme” button sent a custom prompt event:

function makeMeme() {

window.parent.postMessage({

type: "prompt",

payload: {

prompt: "Create a funny meme caption for this image."

}

}, "*");

}

After (MCP Apps): The exact same button now calls a real method using JSON-RPC:

async function makeMeme() {

window.parent.postMessage({

jsonrpc: "2.0",

id: Date.now(),

method: "ui/message",

params: {

content: {

type: "text",

text: "Create a funny meme caption for the image I just uploaded. Make it humorous and engaging, following popular meme formats."

}

}

}, "*");

}

It feels like a small refactor, but it’s actually a big ecosystem-level shift. Instead of UI behavior being tightly coupled to one SDK or one host, we now get:

- Shared primitives

- Shared expectations

- Real interoperability across hosts

This is one of those changes that doesn’t dramatically affect your day-to-day UI code, but it does fundamentally change how this ecosystem can grow. It makes MCP Apps feel less like clever integrations and more like shared infrastructure we can actually build on together.

Try it yourself

If you’re curious about building MCP Apps yourself, follow the guide Building MCP Apps.

And if you already have an MCP-UI server, try converting just one tool to an MCP App. That’s usually the moment when everything starts to really click.

As a reminder, MCP Apps run sandboxed with CSP restrictions, so it’s worth understanding how resource discovery, MIME types, and security policies fit together. The MCP Apps specification is a great reference if you want to go deeper.